Development communication

Development communication refers to the use of communication to facilitate social development. Development communication engages stakeholders and policy makers, establishes conducive environments, assesses risks and opportunities and promotes information exchanges to create positive social change via sustainable development.Development communication techniques include information dissemination and education, behavior change, social marketing, social mobilization, media advocacy, communication for social change, and community participation.

Development communication has not been labeled as the "Fifth Theory of the Press", with "social transformation and development", and "the fulfillment of basic needs" as its primary purposes. Jamias articulated the philosophy of development communication which is anchored on three main ideas. Their three main ideas are: purposive, value-laden, and pragmatic.Nora C. Quebral expanded the definition, calling it "the art and science of human communication applied to the speedy transformation of a country and the mass of its people from poverty to a dynamic state of economic growth that makes possible greater social equality and the larger fulfillment of the human potential".

Melcote and Steeves saw it as "emancipation communication", aimed at combating injustice and oppression. The term "development communication" is sometimes used to refer to a type of marketing and public opinion research.

Definition of Development Communication

1. Development communication, as an interdisciplinary field, is based on empirical research that helps to build consensus while it facilitates the sharing of knowledge to achieve a positive change in the development initiative. It is not only about effective dissemination of information but also about using empirical research and two-way communications among stakeholders (Development Communication division, the World Bank )

2. It is a social process based on dialogue using a broad range of tools and methods. It is also about seeking change at different levels, including listening, building trust, sharing knowledge and skill-building policies, debating and learning for sustained meaningful change. It is not public relation or corporate communication (Rome Consensus of World Bank 2006)

There are five keywords in development communication: dialogue, stakeholders, sharing knowledge and mutual understanding. The first keyword associated with development communication is dialogue. No matter what kind of project, it is always valuable and essential to establish dialogue among the stakeholders. Dialogue is necessary ingredient in building trust, sharing knowledge and ensures mutual understanding.

Development communication has two modes of application: monologic mode and dialogic mode. The participatory model mainly deals with dialogic communication. The monologic mode is broadly equivalent to the diffusion perspective and is based on the transmission model. It adopts one-way communication to send messages, disseminate information, and awareness generation for changing behaviour. The dialogic mode is closely associated with the participation perspective and uses two-way communication methods to build trust, exchange knowledge and perception, achieve mutual understanding and asses the risk and opportunities. Dialogic approaches guarantee that relevant stakeholders have their voice to be heard.

In socio-development initiatives, inclusion of dialogic development communication often results in the reduction of political risks, the improvements of the project design and performance, increased transparency and enhanced people’s voice and participation. For example, many development projects initiated by the Government fail because from the beginning of the development project, key stakeholders were not involved in the preparatory and planning phases. The lack of proper communication at the initial stage generates suspicions among stakeholders and leads to misunderstanding and negative attitude towards the projects. The cause of these problems, and ultimately of the project failure, is the lack of two-way communication.

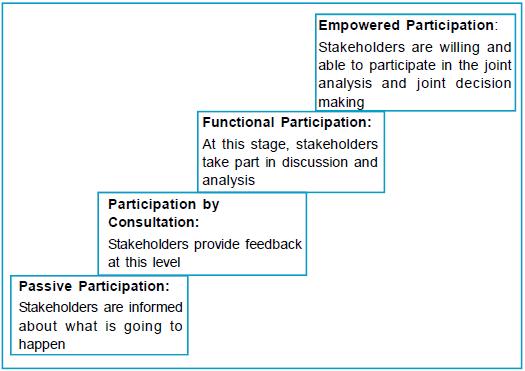

Participation ladder of stakeholders in development communication

Sustainable Civil Society Initiative – Shubh kal

Climate change is happening. The science is compelling and the longer we wait, the harder the problem will be to solve

Shubh Kal, an initiative of Development Alternatives and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation is a pilot project and supports measures that eventually lead to better income, improved resource management, lower carbon footprint and overall reduction in climate vulnerability of the population. This project has three target groups: farmers, artisans and women who are trying to improve their livelihood conditions in the drought-affected Bundelkhand region. The project area has been facing constant drought for the last few years; few livelihood options and low literacy level are major problems and, hence, the initiative has been trying to improve the lives of these three target groups by devising micro projects that are relevant to climate change adaptation. Due to the context, some complexities in the content and to the need for capacity building, here the communication strategy relies mostly on interpersonal and group methods like focus group discussion, knowledge mapping, exposure visits to other relevant project areas, etc. The key stakeholders have been associated with the process from the beginning so that no misunder-standing may take root in their mind. We are hopeful that the initiative will lead to the expected projects results within the timeframe.

The Emerging Participatory Paradigm

The participatory model of communication for social change is mainly a new look at the newly emerging paradigm in development since it emphasises the importance of two-way horizontal communication and need to facilitate the participation of stakeholders in each step for empowerment. ‘Change is now expected to be defined with the people and not for the people, making communication for social change closely aligned with the participatory communication perspective’ (World Bank).

This model favours people’s active and direct interaction through consultation and dialogue. It shifts the emphasis from information dissemination to situation analysis, from persuasion to participation.

Participatory approaches are gaining worldwide importance in development programmes because they offer enough opportunities to any individual right from passive recipients to active agents of development efforts. Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) and Participatory Action Research (PAR) are the two main approaches of development communication. PRA facilitates people’s involvement in the problem analysis process, while PAR aims at placing communities and local stakeholders in the driving seat of development efforts. Till such time as we do not include communication in a systematic and dialogic manner, any approach of communication will not be successful in the large scale. Participatory development communi-cation or the horizontal model of communication opens up new space for dialogue among stakeholders and facilitates the exchange of knowledge, empowering people to participate actively in the process affecting their own lives.

In the participatory approach, engagement of stakeholders is essential for assessing risks, identifying opportunities, preventing problems and identifying the needed change. This is the model communication to asses and to empower are its key focal points. In this model, the media is no longer the central element of communication. It can be used as one of the tools to be used according to the situation. The SMCR model has given way to the two-way model which is more appreciated, where the sender is at the same time the receiver and vice verse. The combination of these elements in emerging development paradigm is shifting its focus from media to people, and from persuasion to participation.

Definition

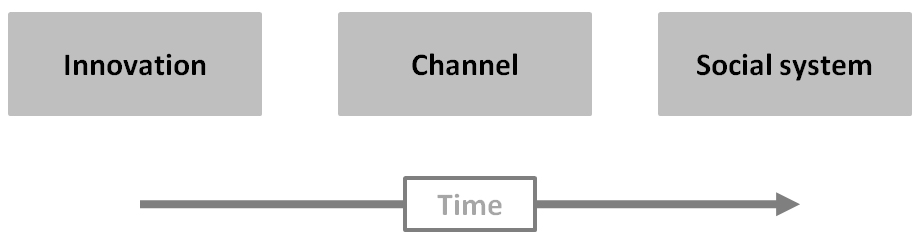

Diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system (Everett Roger, 1961). An Innovation is an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual or other unit of adoption (Rogers, 2003).

Theory

The diffusion of innovation theory analysis how the social members adopt the new innovative ideas and how they made the decision towards it. Both mass media and interpersonal communication channel is involved in the diffusion process. The theory heavily relies on Human capital. According to the theory , innovations should be widely adopted in order to attain development and sustainability. In real life situations the adaptability of the culture played a very relevant role where ever the theory was applied. Rogers proposed four elements of diffusion of innovations they are

Innovations – an idea, practice, or object perceived as new by an individual. It can also be an impulse to do something new or bring some social change

Communication Channel – The communication channels take the messages from one individual to another. It is through the channel of communication the Innovations spreads across the people. It can take any form like word of mouth, SMS, any sort of literary form etc

Time – It refers to the length of time which takes from the people to get adopted to the innovations in a society. It is the time people take to get used to new ideas. For an example consider mobile phones it took a while to get spread among the people when it is introduced in the market

Social System – Interrelated network group joint together to solve the problems for a common goal. Social system refers to all kinds of components which construct the society like religion, institutions, groups of people etc

Who made the decision to accept the innovation? Rogers says that in a social system there are three ways the decisions are taken. He suggested the three ways considering the ability of people to make decisions of their own and their ability to implement it voluntarily, the three ways are as follows..

Optional – Individuals made a decision about the innovation in the social system by themselves

Collective – The decision made by all individuals in the social system

Authority – Few individuals made the decision for the entire social system

Further Roger identifies the Mechanism of Diffusion of Innovation Theory through five following stages

Knowledge :

An Individual can expose the new innovation but they are not showing any interest in it due to the lack information or knowledge about the innovation

Persuasion :

An Individual is showing more interest in the new innovation and they are always seeking to get details or information about the innovation

Decision :

In this stage, an individual analysis the positive and negative of the innovation and decide whether to accept / reject the innovation. Roger explains “one of the most difficult stages to identify the evidence”

Implementation :

An individual’s take some efforts to identify the dependence of the innovation and collect more information about the usefulness of the innovation, then its future also

Confirmation :

An individual conforms or finalize their decision and continue to use the innovation with full potential

Example

During the last years of 90’s the mobile phones were introduced to common people even though it was there in market the cost was much higher. Roger’s theory of diffusion of innovation can be apprehended by understanding how the people accepted and get used for mobile phones. When it was introduced it wasn’t something which comes with 500+ killer applications as today it was merely a portable land line.

Diffusion of Innovation Theory

Diffusion research examines how ideas are spread among groups of people. Diffusion goes beyond the two-step flow theory, centering on the conditions that increase or decrease the likelihood that an innovation, a new idea, product or practice, will be adopted by members of a given culture. In multi-step diffusion, the opinion leader still exerts a large influence on the behavior of individuals, called adopters, but there are also other intermediaries between the media and the audience's decision-making. One intermediary is the change agent, someone who encourages an opinion leader to adopt or reject an innovation (Infante, Rancer, & Womack, 1997).

Innovations are not adopted by all individuals in a social system at the same time. Instead, they tend to adopt in a time sequence, and can be classified into adopter categories based upon how long it takes for them to begin using the new idea. Practically speaking, it's very useful for a change agent to be able to identify which category certain individuals belong to, since the short-term goal of most change agents is to facilitate the adoption of an innovation. Adoption of a new idea is caused by human interaction through interpersonal networks. If the initial adopter of an innovation discusses it with two members of a given social system, and these two become adopters who pass the innovation along to two peers, and so on, the resulting distribution follows a binomial expansion. Expect adopter distributions to follow a bell-shaped curve over time (Rogers, 1971).

The criterion for adopter categorization is innovativeness. This is defined as the degree to which an individual is relatively early in adopting a new idea then other members of a social system. Innovativeness is considered "relative" in that an individual has either more or less of it than others in a social system (Rogers, 1971).

Adopter distributions closely approach normality. The above figure shows the normal frequency distributions divided into five categories: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. Innovators are the first 2.5 percent of a group to adopt a new idea. The next 13.5 percent to adopt an innovation are labeled early adopters. The next 34 percent of the adopters are called the early majority. The 34 percent of the group to the right of the mean are the late majority, and the last 16 percent are considered laggards (Rogers, 1971).

The above method of classifying adopters is not symmetrical, nor is it necessary for it to be so. There are three categories to the left of the mean and only two to the right. While it is possible to break the laggard group into early and late laggards, research shows this single group to be fairly homogenous. While innovators and early adopters could be combined, research shows these two groups as having distinctly different characteristics. The categories are 1) exhaustive, in that they include all units of study, 2) mutually exclusive, excluding from any other category a unit of study already appearing in a category, and 3) derived from one classificatory principle. This method of adopter categorization is presently the most widely used in diffusion research (Rogers, 1971).

Adopter Categories

Innovators are eager to try new ideas, to the point where their venturesomeness almost becomes an obsession. Innovators’ interest in new ideas leads them out of a local circle of peers and into social relationships more cosmopolite than normal. Usually, innovators have substantial financial resources, and the ability to understand and apply complex technical knowledge. While others may consider the innovator to be rash or daring, it is the hazardous risk-taking that is of salient value to this type of individual. The innovator is also willing to accept the occasional setback when new ideas prove unsuccessful (Rogers, 1971).

Early adopters tend to be integrated into the local social system more than innovators. The early adopters are considered to be localites, versus the cosmopolite innovators. People in the early adopter category seem to have the greatest degree of opinion leadership in most social systems. They provide advice and information sought by other adopters about an innovation. Change agents will seek out early adopters to help speed the diffusion process. The early adopter is usually respected by his or her peers and has a reputation for successful and discrete use of new ideas (Rogers, 1971).

Members of the early majority category will adopt new ideas just before the average member of a social system. They interact frequently with peers, but are not often found holding leadership positions. As the link between very early adopters and people late to adopt, early majority adopters play an important part in the diffusion process. Their innovation-decision time is relatively longer than innovators and early adopters, since they deliberate some time before completely adopting a new idea. Seldom leading, early majority adopters willingly follow in adopting innovations (Rogers, 1971).

The late majority are a skeptical group, adopting new ideas just after the average member of a social system. Their adoption may be borne out of economic necessity and in response to increasing social pressure. They are cautious about innovations, and are reluctant to adopt until most others in their social system do so first. An innovation must definitely have the weight of system norms behind it to convince the late majority. While they may be persuaded about the utility of an innovation, there must be strong pressure from peers to adopt (Rogers, 1971).

Laggards are traditionalists and the last to adopt an innovation. Possessing almost no opinion leadership, laggards are localite to the point of being isolates compared to the other adopter categories. They are fixated on the past, and all decisions must be made in terms of previous generations. Individual laggards mainly interact with other traditionalists. An innovation finally adopted by a laggard may already be rendered obsolete by more recent ideas already in use by innovators. Laggards are likely to be suspicious not only of innovations, but of innovators and change agents as well (Rogers, 1971).

Uses and Gratification

Uses and gratification is more a concept of research than a self-contained theory. Even contributors in this field of research find problems with the scope of the research and call uses and gratification an umbrella concept in which several theories reside (Infante et al. 1997). Researchers in this field argue that scholars have tried to do too much and should limit the scope and take a cultural-empirical approach to how people choose from the abundance of cultural products available.

Critics claim the theory pays too much attention to the individual and does not look at the social context and the role the media plays in that social context. Rubin (1985), as cited in Littlejohn (1996), suggests that audience motive research based on uses and gratification research has been too compartmentalized within certain cultures and demographic groups, leading to the assumption this has thwarted synthesis and integration of research results, which are two key ingredients in theory building.

The uses and gratification theory is a basic extension of the definition of an attitude, which is a non-linear cluster of beliefs, evaluations, and perceptions. These beliefs, evaluations, and perceptions give individuals latitude over how they employ media in their lives; in other words, how individuals filter, interpret, and convey to others the information received from a medium. Basically, a person’s attitude toward a segment of the media is determined by beliefs about and evaluations of the media. A key to this research is that the consumer, or audience member, is the focal point instead of the message. The research views the members of an audience as actively utilizing media contents, rather than being passively acted upon by the media, according to Katz, Blumer, and Gurevitch (1971) as cited in Littlejohn (1996). When audience members, not the media, are the action takers, the variations taken from the messages received are the intervening variables.

A core assumption of uses and gratification research is the assumption that individual needs are satisfied by audience members actively seeking out the mass media (Infante et al., 1997). Rubin (1983), as cited in Littlejohn (1996), designed a study to explore adult viewers’ motivations, behaviors, attitudes and patterns of interaction to see if behavioral and attitudinal consequences of the viewer could be predicted. In 1984, the researcher identified two types of television viewers. The first type is the habitual viewer who watches television for a diversion, has a high regard for the medium, and is a frequent user The second type is the non-habitual viewer who is selective, likes a particular program or type of programs and uses the medium primarily for information. The non-habitual viewer is more goal oriented when watching television and does not necessarily feel that television is important. Rubin (1983) argues that habitual viewers use the medium as a companion and that non-habitual viewers are more actively involved in the viewing experience (Littlejohn, 1996).

Expectancy-value theory

Another theory to consider under this umbrella of uses and gratification research is expectancy-value theory from information-integration theorist Martin Fishbein (Littlejohn, 1996). The researcher proposes there are two kinds of belief; belief in something and belief about something. The example used by Fishbein is the person who believes in marijuana as a recreational drug or the person who believes that using marijuana will move on to other drugs and serious crimes in order to continue the habit.

In Fishbein’s theory development, attitudes are different from beliefs in that they are evaluative and are correlated with beliefs and predispose a person to behave a certain way toward the attitude object. The two beliefs about marijuana mentioned above would change dramatically if more serious drugs and crime were evaluated as bad. Also cited in Littlejohn is Philip Palmgreen, an early uses and gratification researcher, who claims that gratifications are sought in terms of a person’s beliefs about what a medium can provide and that person’s evaluation of the medium’s content (Littlejohn, 1996).

Comments

Post a Comment